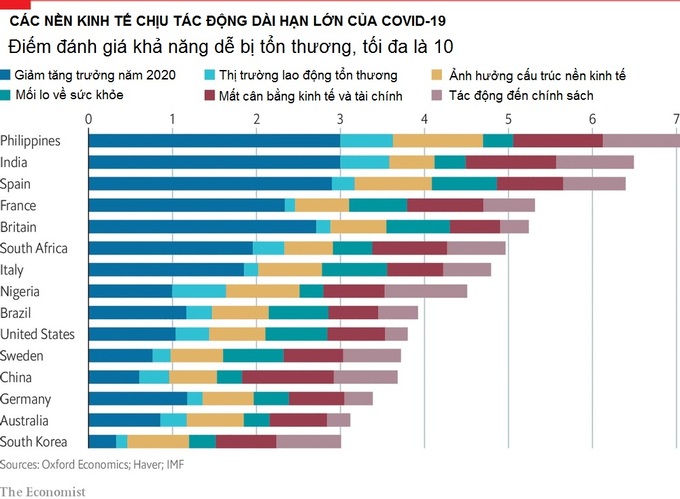

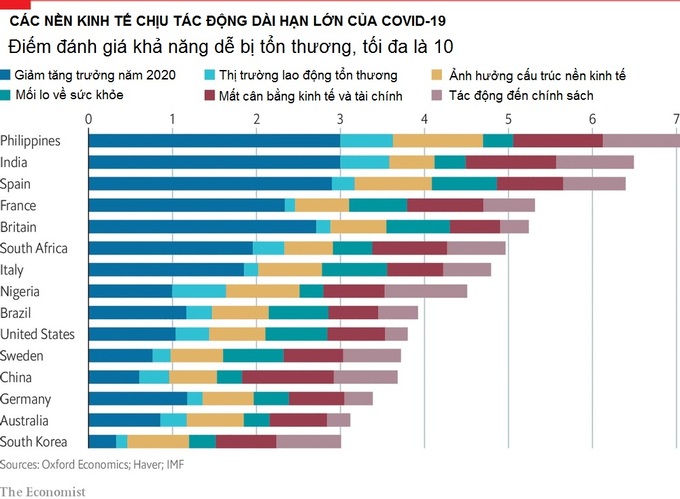

Research by Oxford Economics shows that the Philippines, India and Spain are the three countries with the greatest long-term impact of the pandemic.

Modeling by Oxford Economics sheds light on the long-term effects of Covid-19. This study predicts which countries are the most vulnerable to the long-term economy, and which countries may recover early.

The researchers gathered evidence from past crises, including Ebola and SARS, and the 2007-2009 global financial crisis, to create 31 measures of economic vulnerability. This includes areas such as economic structure, GDP growth and consumer confidence.

After calculating, they predict that, on average, emerging markets will suffer more in the long run than advanced economies. The most important predictors, like the decline in GDP growth this year, tend to be larger in advanced economies. But other factors, such as labor market rigidity and limited fiscal support, threaten emerging markets more.

However, going deeper, there are also major differences between emerging and advanced economies. The Philippines and India have particularly bleak growth prospects, while China and Brazil are expected to perform better.

The Philippines is ranked worst overall in the study, largely due to its high unemployment rate, lack of skills, and a dependent on tourism labor market. Among the advanced economies, researchers said the UK, Spain and France will take longer to grow again than Australia, Sweden and the US.

By region, the Middle East and Latin America have the worst recovery prospects, followed by Africa. North America is the least vulnerable region thanks to relatively low GDP declines and strong fiscal stimulus packages.

European countries occupy the lowest ten positions for advanced economies on the Oxford Economics scoreboard. But there is also a disparity among the members. For example, France ranks as one of the most vulnerable countries in the study, largely due to weak GDP growth and low consumer confidence, but neighboring Germany scores higher than both. . side.

As well as identifying why some countries recover faster than others, research shows how governments can best prepare for future shocks.

For example, some emerging markets may consider diversifying tourism, while developed economies may reduce dependence on the hospitality industry to spur consumption.

At the same time, there are reasons for optimism. In previous outbreaks, growth averaged 3 percentage points lower in crisis-impacted countries, but growth thereafter was slightly better than the five-year average prior to the crisis. In other words, there is room for recovery, but some countries will rise higher than others.

Phiên An (theo The Economist)